This piece originally ran in Stereogum’s The Black Market on July 2020. This is an annotated version.

In 1999, Thomas Andresen said the following to the Russian webzine Vae Solis: “[It was] a good name for us at that time.”1

You might recognize Andresen as a member of Algol, a Norwegian band that united ‘90s waves of death metal and black metal on its sole full-length, Entering The Woods Of Enchantment. Or, you might know him as the voice of the reconstituted Fester, another black-plus-death early adopter that was exhumed in 2012 for A Celebration Of Death.

Both of those groups have okay names. Algol, in particular, is uniquely nerdy no matter which disambiguation adventure you choose. Maybe that’s why Andresen was fond of it, stating in the same interview that “the last guitar player we had (Kjell) tried to [change the name], but no way I would let him do it. ALGOL will be with me and die with me.”

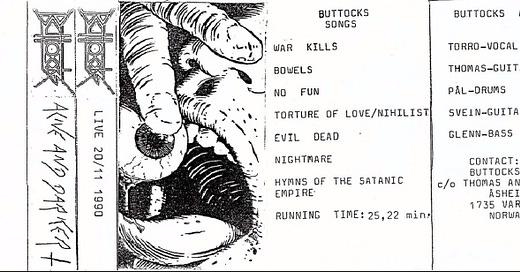

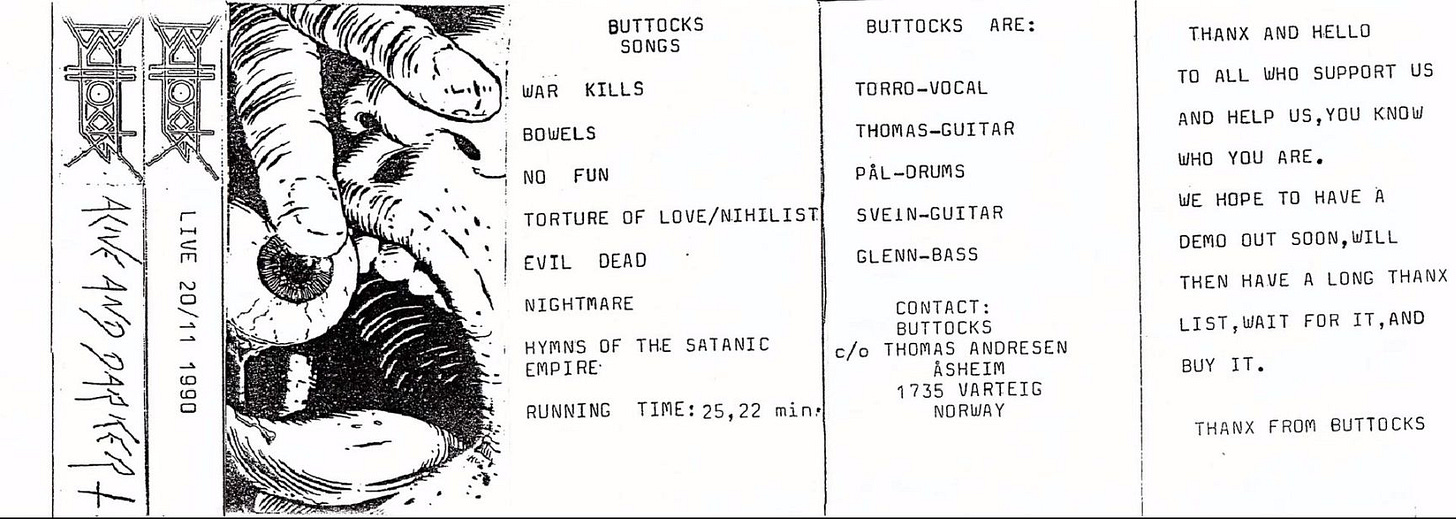

Considering how painful the band naming process can be, I don’t blame anyone for taking a “from my cold, dead hands” stance when they find a name that works for them. Isn’t that right, Entombed? However, when Andresen said it was “a good name for us at the time,” he wasn’t referencing Algol. No, he was talking about Algol’s previous incarnation: Buttocks.2

I’ll let that sink in.3

Buttocks wasn’t even the first band named Buttocks. That honor goes to West German punk band the Buttocks. That Buttocks released a posthumous compilation in 1985 titled Fuckin’ In The Buttocks.4 There’s an earlier example of a musical buttocks on the books: Charlies, a lightly prog Yardbirds-y rocker from Finland, named its 1970s sophomore outing Buttocks. Imagine not even grabbing Buttocks first.

How did the death metal Buttocks settle on its name, then? According to Andresen: “Well, the first name we had was SEANCE, a really good but not very original name. At that time we also [played] a lot more [hardcore] music. We had SEANCE for about 3-4 months. Then the singer [left] and we changed the name to BUTTOCKS.”

Hm. Andresen and company landed on Seance in 1989, a year before the Swedish salt-rubbers adopted it. The only other Seances I can find that held the name earlier were the Swiss EBM entity Séance, gothy British post-punkers Seventh Séance, and, maybe, Pittsburgh power metal quintet Seance. Maybe: The power metal Seance was also minted in 1989, but the quintet didn’t release anything until 1992, and then … who knows. Its one, surprisingly solid, EP Pray For Me is it. Since it’s a repress candidate, someone should convene a meeting and try to contact them.

Anyway, while it’s possible that 1980s Norway was swimming in bar bands named Seance, the available fossil record shows that Andresen’s crew probably could’ve stuck it out with its first choice if they didn’t mind the non-metal antecedents. I mean, why not, there are 20 metal bands named Cerberus.

Instead, they powered on with Buttocks, releasing four demos between 1990 and 1991. The last one, Urcemurcel Turkus, is even pretty good for what it is. In a fairer world, it would’ve earned Buttocks a backing. Ah, but the band was named B-U-T-T-O-C-K-S.

“In the beginning many bands [are] insecure about the way they shall go; so were we,” Andresen said. “It started out as [a] fun band and developed into a bit more serious one.” (I emailed both Fester and its previous PR team. I was unable to reach Andresen for comment.) When it came time to buckle down, to hunt for greater success without the burden of Buttocks, the band became Algol.

Here’s the thing: While the path to and from Buttocks is one of the more inscrutable journeys I’ve come across lately, it’s not that unusual of a name for a metal band. I mean, metalheads reliably chip in a few entries into A.V. Club’s “Worst Band Names” series. Of course, metal isn’t the only genre plagued with goofball names. Hello, Sniff ‘N’ The Tears. But, since metal already has such a high barrier of ludicrousness that listeners need to scale to in order to enjoy its sound and presentation, names that would sink bands in more commercially minded genres are allowed to persist. Metal bands with bad names get signed. Metal bands with bad names release albums. Metal bands with bad names have careers. It doesn’t seem like it’s much of a penalty. To an extent, it’s just another element of the overall heavy metal experience.

Indeed, when constructing this very column, we typically come across a handful of Buttockses every month. A sampling of July’s abundant harvest: Nug, Undeath, Amateur Podiatry, Fuckopalypse, and Latrines. Would you namecheck any of those bands on a blind date? (“Actually, in its liner notes, Latrines nods to Georges Bataille, who you may know as the author of The Solar Anus. Hey, don’t leave, the breadsticks just got here!”) And yet, some of those bands are good.

Because of this not uncommon disconnect between band name and music quality, I’ve become so inured to bad names that they rarely catch my attention. To wit, I was legitimately excited to learn there’s a new Arsebreed album on the horizon. Granted, as the Name Of The Year Bracket reliably demonstrates, this is all subjective. Maybe you think Arsebreed is a great name. Whatever. The point, though, is that the ridiculousness of that one doesn’t even register anymore.

This is the way of life in a culture where the biggest band is named Metallica and proto-metal forebears include Sir Lord Baltimore and Vanilla Fudge, names that were lovably dumb long before it felt like metal was scraping the bottom of the coffin for original monikers. I just expect metal bands, in their never-ending quest to escalate extremity and relive the past, to land on some pretty bad names. As a consequence, it’s like I’m blind to band names. Well, most of them.

How did I get like this? Do band names in metal matter? And what happens when you choose to opt out, settling on a symbol instead of a name? To help answer these questions, I reached out to Anthony Shore.5

Shore is the “Chief Operative” of Operative Words, an agency he started in 2009. The bungalow elevator pitch is that he helps interested parties name themselves and their products.6 In other words, he’s a professional namer and has been working within that space for over 25 years. The gig, though, is a bit more complicated than abracadabra-ing appellations,7 involving additional elements such as teasing out “novel descriptors,” constructing “nomenclature systems,” and performing tasks like “global trademark and domain screening.” Nevertheless, as human nature demands, you now want to see Shore’s goods: Yum! Brands, the corporation that operates KFC, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell,8 the Habit Burger Grill, and WingStreet, is one of his. Qualcomm’s Snapdragon, the series of semiconductors that became a smartphone staple, was a naming project he helped direct. There are literally hundreds more.

“I’m proud of some names I’ve done lately,” Shore tells me over Zoom. “A company that used to be called Software Motor Company is now called Turntide. They make super efficient motors. If the engines were to be deployed across the globe, they would immediately have an impact on climate change. It’s really hard to come up with a name in the category of energy efficiency or sustainability. It’s kind of like metal band naming where you’ve got really tight parameters and the challenge is to find something different.”

Shore’s naming process, which was detailed in a New York Times Magazine piece in 2015, is exhaustive. Leaning on his educational background in linguistics and its computational cousin, he comes up with hundreds if not thousands of names for every project, utilizing tools ranging from in-depth interviews with clients to artificial intelligence (AI) to old-school creative techniques that are like brain games for word nerds. “To name well, you must name abundantly,” is the first line in his blog post “How To Name: Explore Concepts, Not Words.” It might as well be his operating principle. He’ll go to great lengths to get a good name.

“I’m a big believer in technology, software as an adjunct to creative thinking,” Shore answers after I ask how he uses artificial intelligence.9 “I like relying on software to help me discover things that my one wee brain could not discover itself.”

As an example, Shore walks me through the different facets of a computer-based approach. “Let’s say I like the word ‘gray.’ I can call up a database of 30 billion words and say, ‘Why don’t you tell me 5,000 nouns that pair with the word gray in real-world usage.’”

“That, in and of itself, is wildly inspirational, because it’s showing me all of these different ways that gray has naturally paired with other words,” Shore says. “And some of them are going to be trite or so commonplace that they’re boring. But other associations may not be. You’re tapping into the minds of millions because this database is based on real-world text output of how people have talked or typed.”

That sorted database is just the start. Shore will combine the words he has found with other promising candidates pulled by the same method. He’ll then concatenate the lot, creating a fresh list of names adhering to a trainable logic that he’ll upload into a neural network. “The neural net looks at these combinations and words and it starts coming up with its own ideas. It’s seeking to mimic, but not duplicate, what I fed it in the first place. It’s coming up with new ideas that are original and yet they’re based on something that has already been done. And so the neural net offers the opportunity to do a corpora exploration, an exploration of how words associate and collocate with real-world speech.” By adjusting the neural net’s “temperature,” or its “relative creativity,” he can refine the output.

Not that Shore is bound only to AI. He demonstrates how one could achieve the same effect with pen, paper, and a resource like WordNet, Princeton University’s lexical database for English. I listen as he leaps from word category to word category, node to node, like a linguistics version of an Uncharted game, quickly transforming “sadness” into “catatonia.” “By going up and down, by looking at what other nodes you can explore, you can open up entire worlds of associations,” he says. “You’re discovering entire domains of meanings and words that are all related.”

Still, while these processes can help hurdle the word fatigue endemic in industries prone to mimic proven successes, choosing a good name is a trickier procedure. “Naming is difficult and it’s fraught,” Shore reminds me. “It’s very easy for naming projects to run off the rails.” And, I have to think that’s because of the underlying complexities of names in general.

In “What’s In A Name?,” a three-part series that ran on the New York Times’ Opinionator in 2012, Errol Morris dives into names, the associations we attach to them, and how they’re used to either substantiate or subvert identity. In the first piece, Morris unpacks an interesting thought-nugget found in philosopher John Stuart Mill’s 1843 work A System Of Logic: Ratiocinative And Inductive. Mill lays the groundwork for his argument by quoting Thomas Hobbes. Here’s Hobbes’ hot take from his 1655 book De Corpore:

A Name is a word taken at pleasure to serve for a mark, which may raise in our mind a thought like to some thought we had before, and which being pronounced to others, may be to them a sign of what thought the speaker had before in his mind.

And here’s Mill’s million dollar question: “Are names more properly said to be the names of things, or of our ideas of things?”

As Errol Morris points out, John Stuart Mill thinks names are just the names of things. Morris pulls these quotes as evidence: “Proper names are not connotative: they denote the individuals who are called by them; but they do not indicate or imply any attributes as belonging to those individuals.” And then Mill winds up for the knockout blow: “Proper names are attached to the objects themselves, and are not dependent upon the continuance of any attribute of the object.”

And it’s like, sure, John Stuart Mill. I guess so. No matter the associations that a name takes on, the name is still the name of the thing. And, if something changes, the name doesn’t necessarily have to change, although I bet Batushka could offer some insight here. Fine. Makes sense.

I would, uh, sure like to wear my Isis shirt out in public again, though.10

“Names are fluid,” Shore reminds me before I can bore him with my Mosquito Control laments. “Another way to look at it is that names are absorbent. Names absorb the qualities and associations of the things that they refer to.”

So … are band names really not connotative? This is when something as elemental as naming becomes a bit of a brain sprain.

Consider the following sentence: “Decayed Flesh sounds like classic Suffocation.” My intention is to use Suffocation’s name as a stand-in for the identifiable stylistic elements of its music. “Suffocation,” in this sense, means a grimy, brutal death metal sound. By modifying that name with “classic,” it also becomes shorthand for a value judgment. In turn, by aligning Decayed Flesh with Suffocation, it elevates Decayed Flesh’s perceived standing.

Now, I could make that same statement by delving into the music theory behind why I think Decayed Flesh is good, and I would be a much better writer if I did. That said, provided that you and I know Suffocation’s music and appreciate its “classic” period, I can approximate the same effect with two words. There’s a lot of data packed in that name if our assumptions align, which is why FFO and RIYL sticker marketing is effective.

Here’s my [*extremely Lil Wayne voice*] Millian question, then: Does the example above demonstrate that Suffocation has name recognition or is its name simply an easier way to convey that Suffocation has great music recognition? Hold on, let me run that through the galaxy brain filter. Which is more important in metal: Name recognition or music recognition?11

I tend to think that music recognition is more important. Let me now back away from that extremely controversial opinion.

I’ll concede that I’m being irrationally optimistic since I’m basically saying that good, important music will eventually be recognized. It would be nice if that world existed, right?

I have to reiterate that this take, and in fact anything written in this intro, only holds true for metal and metal band names. How names and identity function in others spaces is a different bag of beans.

I’m an idiot.

With that out of the way, it’s also worth making an important distinction: To me, name recognition is often a byproduct of music recognition. While inextricably linked, the two are not synonymous. Bands that court controversy or focus on theatrics can gain name recognition without having music recognition. You can know of and appreciate GWAR without having heard a shred of its music. But, by and large, we know bands’ names because we know their music. In a longterm sense, the quality of the name isn’t as important.

That’s not to say that careers can’t be hamstrung by a bad name. Italy’s Gory Blister has been making competent technical death metal for decades. Its first two albums are pretty good. Its name sucks. (Yes, to be fair, we did name a band Fatty Carbuncle and my given first name is pronounced like a drunk struggling to read an eye chart.12 Touché.) It sucks so badly, I wouldn’t be surprised if it keeps people from listening to the band. To put it another way, that’s when a name is important: onboarding new listeners, inspiring that initial instance of engagement. There’s so much music, why would you waste time on a band with a name that not only doesn’t grab you, but woefully misses the mark unless it comes to you via a convincing recommendation? (Again, first two albums.)

However, is that the fault of the name alone? Could it also be a failure of marketing and other exposure-widening avenues? Because, anecdotally, it feels like metalheads will acclimate to ridiculous names if the music is good enough and will normalize bad names if that music is influential enough. If that’s accurate, then band names aren’t “good” or “bad” so much as they are familiar or unfamiliar.

To drive this home, take a look at Empath, a visualized “band similarity index.” If you’re not a heavy metal convert, this must look like a Scrabble dictionary for sadists. And yet, the bigger, bolder names are so familiar to your average metalhead that they’re no longer proper nouns but whole chapters in certain styles’ stories. It’s the smaller names, then, the ones that haven’t reached the same commonality within the community, that look weird. What is “A Million Dead Birds Laughing”? That band’s fanbase knows, though, and if the group breaks out and becomes influential enough, so will the rest of us.

“Words have different associations and have different import at different levels,” Shore explains. “So, to a single person, they’re going to have their own idiosyncratic associations with their name based on their own experiences. Then, there may be a group of people around them that collectively have certain associations with a name. If you keep expanding that circle outward, you’re going to find that these associations become more and more complex. It’s something that’s governed at the individual level, group level, tribe level, community level, society level, language level, and all of these different levels. You’re going to find that the shades of meanings are different.”

Later, Shore sums it up like this: “Your familiarity will help you see nuance.”

Some bands successfully leverage a listener’s familiarity, telegraphing what they’re trying to get across through their name. Think of all of the bands that derive their name from influential song or album titles. But, I also wonder if that kind of familiarity can backfire.

For example, I got a promo for Evil Warriors’ new EP, Schattenbringer. Based on the band name alone, I had the German four-piece pegged as a rehash thrash band that maybe mixed in some elements of death metal. There’s a reason for that. At the time I’m writing this, 173 bands in the Encyclopaedia Metallum have a two-word band name that starts with “evil.” 67 of those have a variant of “thrash” listed within their genre tags. 61 have “death metal.” (The pool of two-word names that end with “warriors” is much smaller, counting only 14 bands. Of those, the leading genre is, as expected, power metal.) For your appraisal, here’s Schattenbringer:

While Evil Warriors’ Encyclopaedia Metallum genre is “Death/Thrash/Black Metal,” which is cheating and probably a vestigial categorization held over from its demo days, Schattenbringer sounds to me like straight-up black metal. And, I’ve got to say, this still flummoxes me. How are you guys named Evil Warriors! I almost skipped this!

So, much to the delight of John Stuart Mill’s ghost, I have to ask: Is my familiarity Evil Warriors’ fault? No. These aren’t associations that the name has absorbed so much as they’re associations I’ve absorbed by way of cultural forces. You can see this more clearly in band names that look weird to English speakers but make sense in their native tongues. the the Myth is a perfect example of this.13 I guess a supremely savvy band could try to control for an intended listener’s familiarity when choosing a name, but these kinds of complications are why I don’t blame bands that try to skip the naming step altogether.

(0), a Danish quintet, released SkamHan on Napalm Records this year.14 It’s a neat mix of post-metal and black metal with its own flavor of avant-garde inclinations. When I ask over email why (0), a name the group writes out in its Bandcamp URL as “parentes0parentes,” the band answers, “Because we felt that (0) was the closest to a void band name we could get.”

The origin of (0) can be traced back to a philosophical discussion that the band had upon forming. “We asked ourselves this question: Why do band names even exist? The answer would be about things that have nothing to do with music,” the band writes, getting to, ahem, the heart of the matter much faster than I have. “Band names are used for communicating about music, and it’s used commercially. Thus (0) appeared in a conversation about a band name. We wanted a name that emphasizes that the music is the center of attention. No word could really express that, so we ended up with as little as possible — a zero in parentheses. Ideally it would have been just a void, but even to us it was obvious that that would probably make things too complicated for the listener.”

I asked Shore for his assessment of (0). “That’s one of those situations where the name is going to have certain meaning to people who are already tuned in to the ‘in’ language,” he answers. “It’s cryptography. Or, a shibboleth. It’s a secret handshake that’s within a name. If you know how to call it parentes0parentes, then you’re in.”

This type of “secret handshake” is a heavy metal specialty, of course. It might even be heavy metal bedrock, a quality essential to the fandom. It’s that fundamental metal feeling that you get it and others don’t. (It must be said that groups have used that handshake for more nefarious means, such as the racist bands that hide in plain sight, subtly nodding to likeminded donkuses through context clues.)

(0) and other no-namers like 01101111011101100110111001101001 seem to be after something bigger than just the handshake, though. Refusing a name almost seems like a reaction to capitalism and the commodification of identity.

Be that as it may, (0) is still, you know, out there selling records. This is something that isn’t lost on the band. “(0) is not a commercial project, but we do acknowledge that signing with a major label like Napalm Records is a huge leap into the commercial world of music. It’s a paradox which is both challenging and interesting, and it’s something we’ve spent a lot of time discussing internally in the band. One could argue that the ultimate way of being anti-commercial is by never releasing any music. We briefly considered that, while recording our 2017 EP, but found the idea a bit too extreme. Instead we focus on being completely honest when creating music, and letting the art guide us instead of commercial consideration.”

Shore also recognizes (0)’s intriguing duality. “There’s a tension there, a dynamic at play. On the one hand, it’s not helpful if people literally don’t know how to refer to it, at least in speech. When radio was a thing, that would’ve been a real obstacle. In this day and age, when a lot of stuff is written out, it kind of doesn’t matter. On the other hand, it’s always valuable having something that’s descriptive.”

And, to an extent, (0) has already seen a return on that value. While the band acknowledged that the name made things more difficult “in terms of promotion, search engines, and streaming platforms,” it still managed to generate a buzz just by being different. “The name did attract some attention in Denmark after the release of our EP and was a partly responsible for the hype around the band — even though [it was] unintended.”

This reminds me of something Shore said early on in our conversation: “I say, and others who also name things generally believe, that a great name is never going to make up for a shitty project. And, a bad name will typically not torpedo the potential success of a good product.” And yet, he asks, if you’re given the choice, shouldn’t you choose a name that won’t create “friction in terms of how you’re perceived?”

Which, of course, brings us back to “good” names. What is a good name? “A good name is forever,” Shore responds. “A good name will never wear out. A good name will never outgrow the thing that it refers to. I look at the staying power of names, the name’s ability to always be relevant. And, to some extent, to always keep people engaged. Some names are a dialogue and others are a monologue.”

Is (0) a good name? For what it’s worth, I like it, although I’ve been influenced by the band’s canny explanation. It’s certainly a dialogue, raising interesting questions regarding the role of band names in metal. And, for now, it’s unique, with only a few other bands employing the same concept. A (0), 0N0, 0, 0-Nun tour package would be the ultimate music recognition experiment. But will (0) scale with the band? Will (0) still seem unique years from now? (Years, he said. In the middle of a pandemic.) That’s what we can’t see.

My takeaway, then, is that it’s hard to get a band name right because it’s hard to envision where you’re going to be in the future. After all, you never know what is going to go wrong. I agree with Shore that you should at least try to find a name that truly speaks to you and the people you want as supporters. You could end up with a name that last forever. Or … you could end up naming your band Buttocks. A good name at the time, right? Then again, here I am, writing about Buttocks all of these years later.

Remember when you could actually find stuff on the internet? Those days were fun. To write this kind of piece today, you’d have to forego Google and pray that one of the zine repositories, such as The Corroseum, scanned a ye olde Q&A. I really don’t know how you’d it otherwise. I mean, there’s no Newspapers.com for Geocities websites.

Buttocks was the, ahem, butt of a lot of jokes around the Black Market water cooler. We couldn’t fathom how and why a band would go from the perfectly cromulent Seance to BUTTOCKS. This whole intro was supposed to be riffing on that, and then it sort of spiraled into what you’re reading today.

Elon Musk ruined this phrase forever. I will also never forget when Helen Zaltzman, upon encountering Musk’s name for the first time, said, “Isn’t that what comes out of a civet?”

You can’t even imagine how overjoyed I was when I uncovered this tidbit.

Again, these days, I wouldn’t wait so long to introduce a talking head. That said, I think the shaggy dog intro kind of works. Buttocks is a head-turner. Who knew?

I wish I remembered how Shore even came into my orbit. Oddly, he taught me how to pitch better by asking what the tone of the column would be and to share some examples. I still provide that information to this day.

Ian…

That’s how you hyperlink, kids.

This is, like, one of the few applicable use-cases for LLMs.

Still can’t even wear it to the gym.

I am absolutely on my bullshit here.

I’ve used this as an icebreaker and end up explaining it every time. “E-N.”

the the Myth is another Black Market water cooler band.

I have a good working relationship Napalm’s PR arm, so I’d try to find landing spots for bands I found interesting. This one came along at the perfect time.