This piece originally ran in Stereogum’s The Black Market on March and April 2021. This is an annotated version. It is also lightly edited to conjoin both parts.

A Toronto leather store. A pop duo eternally chasing hits. A United States Senate hearing. Alanis Morissette. What’s the connection? Somehow, this:

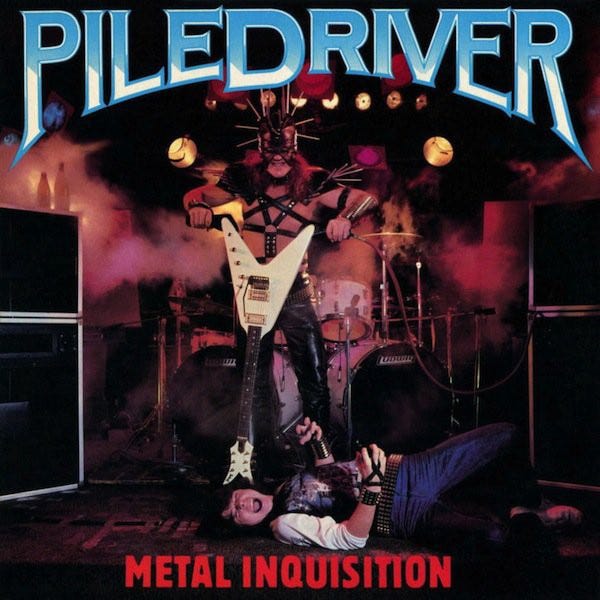

That’s the cover for Piledriver’s 1984 release Metal Inquisition. In a way, this is the story of how that cover got made and ended up adorning one of the most ridiculous and unlikely heavy metal albums of the ‘80s. In another, it’s a story about how one link in a chain can end up connecting so many other things. But, most of all, this is a story about someone who took a job fronting a fake band and then spent decades trying to turn it into something real.

And here’s the ironic part: That person, who sang on the record, who would eventually go on to portray the bespiked “Piley” and play concerts across at least three continents, is not pictured on that cover. In his telling, that would be the first iniquity of many, as if the breaks in his heavy metal career were the kind bestowed by a monkey’s paw. But it wasn’t always like that. No, long before Metal Inquisition went on to sell, by some estimates, 500,000 copies, long before he’d don the roofing spikes during an exalted revival, Gord Kirchin fell in love with music.1

“Surely seconds after I was born I received my first pair of drumsticks,” Kirchin writes over email. By age four, Gord was the proud owner of a Ludwig snare, set to follow in the paradiddles of his father who was drum major of the Governor General’s Footguards on Parliament Hill. The snare wasn’t the only way the elder Kirchin set up his son’s musical foundation.

“My dad was often away doing that ol’ Navy thing, and he was base DJ up north and would mail me home all kinds of promo 45s and albums,” Kirchin remembers, noting that his father also logged some reps on the Canadian bar band circuit. “Thanks to those mailings, the Beatles were gods for me, deeply and profoundly. I fetishized every dot of every image [on those albums] and air-band rocked along with them with a tennis racket or a broom more than my snare drum.”

In between shredding oxygen, Kirchin was developing musically, mapping out Beatles melodies on his grandmother’s upright piano and nailing the rhythms of the Royal Guardsmen’s “Snoopy Vs. The Red Baron” on his Ludwig. But, like his racket-strums suggested, he also was tapping into an irrepressible showmanship that coursed through his veins. “My earliest musical memory as a toddler is cracking my parents up by constantly rambling around the house singing ‘hang down your head Tom Dooley,’ giggling at the dichotomy of a child singing about a man’s corporal punishment by hanging like it was a nursery rhyme. My parents had a great sense of humor.”

As he grew older, Kirchin’s interest in music became an obsession, one that nurtured a curiosity for all aspects of music production. “It was then I occasionally put down the sticks and picked up picks and gradually began exploring guitar and bass, and tape recorders! While my friends were playing tag, I was figuring out that a microphone’s sounds bassier the closer you inch it towards the sound source. As long as I can possibly remember, music and how it’s made was a major part of my life and concerns.”

Kirchin kept logging his tag-less 10,000 hours. He made a breakthrough by finally nailing the drums on the Dave Clark 5’s stomping “Bits And Pieces.” And then, he found the heavier stuff. “A major moment in my metal development was dropping the needle on the song that would assault my ears and resonate for a lifetime: ‘Gypsy’ by Uriah Heep. Oh. My. God. That is so LOUUUUD! I thought. That it made me vibrate to the center of my being felt like a true epiphany: HEAVINESS RULES!”

With Kirchin’s ringing ears now primed for hard rock, the kid across the street initiated the sacred rite of older sibling music. He introduced preteen Gord to a couple albums borrowed from the kid’s big brother: Alice Cooper’s Easy Action and Love It To Death. Kirchin fell hard. A spark was lit, a Big Bang of hard rock. That said, not everyone was on board with his new fascination.

While Kirchin’s parents didn’t mind the morbidity of “Tom Dooley” and let their kid watch the odd horror flick, Alice Cooper was something else. Kirchin’s father, “a George Jones, Waylon Jennings hardcore western drinkin’ fightin’ man,” wasn’t amused. “I took more than a few beatings for being found with mascara spiders on my eyes as I slithered around my room pretending a rolled up towel was a snake while I was acting out ‘Dead Babies,’” Kirchin recalls.

You couldn’t keep the budding hard rocker down, though. And, true to form, Kirchin wouldn’t have to wait much longer to get jumped into band life. In ninth grade, Gord had his first “paying gig” playing drums. He also gained some experience in other areas. “The gig produced my first ‘girl’s actual phone number’ and the mindblowing activity known as ‘frenching,’ so, yeah, that night I knew, ‘Okay, this is it! I’m a rock star now.’”

However, it wasn’t all roses. “l also got my first taste of ‘the business’ that night, too,” Kirchin writes. “As we were heading on a break between sets, a couple of dudes asked if it was cool for them to play a couple of tunes while we were on our break. I figured, ‘Sure, man, you keep ’em dancing while I discover tonsil hockey out back.” Gord came back to find his gear destroyed. “My drums were pooched and the amps trashed. But… look at all the lipstick all over my face! So that’s rock and roll! I get it now. The first of a million bad decisions and burns in the business, because I’m a ‘nice guy.’”

Still, as soon as Kirchin heard “an audience applauding loudly and appreciatively after an original song,” the die was cast. “That was it. Done. I knew, ‘This will be my life.’ I can still feel the heat and humidity of that July afternoon when I actually ‘connected’ with the audience at our local outdoor hockey rink for about 35 kids. It was momentous for me not only in the moment, but later that night as I was in the floor audience for Cheap Trick and Kiss, and all I could think about or hear in my mind was that raucous and heartfelt applause for my song, and looking around the audience thinking someday… someday… I’ll be up there and this many [people] will applaud my songs.”

High school bands eventually became bar bands as Kirchin tried to catch on as a working musician. “I came up in the Ottawa bar scene, cover bands. That I was growing as a musician and vocalist, working towards becoming a musical source rather than a recipient, and gaining stage experience, I reveled in the power and ability to capture an audience and transport them out of themselves for an evening. Sheer magic. As I climbed up the ranks, that has always been the impetus: to entertain and lift spirits.”

Kirchin found his way into one of the bigger cover bands in the area as a bassist and singer on the “heavier” material. The band’s name indicated some of its members’ career intentions: Mainstream. It also happened to contain two other notable Ottawans: Leslie Howe and Louise Reny. And this is where our story adds a few more links to the chain.

In a now-archived bio, Leslie Howe says he and Louise Reny met in high school and the two “started playing in bands around 11th grade.” “We’re completely compatible musically,” Howe added, “but we fight as much as ever.” A Detroit Journal profile on Reny seems to suggest that Mainstream was one of a few “Led Zeppelin cover bands” that both players cycled through in Ottawa. “Once I started writing my own songs and going into a recording studio,” Reny said, “I could draw on all these other styles I used to copy.” Indeed, after Mainstream, both players would demonstrate that they had a canny knack for summarizing sounds and trends. Any trend, really. Even one festering in the scuzzier gutters of heavy metal.

According to the also-archived Canadian Pop Encyclopedia, Mainstream ran from 1975 to 1983. In a CanadianBands.com bio that acknowledges input from Howe, Howe and Reny initiated the split because they “were growing disenchanted with the direction the band was [going] and decided to try it on their own…” Soon, they were headed down a more synth-laden dance pop direction under the name One To One. They circulated demos of originals recorded at Howe’s home studio. (I was unable to contact Howe or Reny for this intro.)2

The demos caught the ear of Clive Corcoran, who the Canadian Pop Encyclopedia also cites as the duo’s manager. He’d eventually sign One To One to Bonaire, an international label and management company that Corcoran co-founded in 1985 with Carl Leighton-Pope, a promoter, agent, and manager of acts running the gamut from Dire Straits, UFO, Camel, Bryan Adams, Loverboy, and later, under his Leighton-Pope Organisation, the Chippendales.3

The first slate of releases for Bonaire’s label and publishing arms consisted of three bands: One To One, the Glaswegian AOR group Strangeways, and Oakville, Ontario prog rockers Saga. Turns out, Corcoran and Saga already had quite the history. In fact, the rumors about that history are key to this story. I can’t believe I’m writing this, but in order to understand how Piledriver’s rabid heavy metal came to be, we first have to take a spin through Saga. By the way, this is Saga:

In the United States, Saga might be remembered best for their top-40 single “On The Loose,” which made MTV’s rotation, or Steve Negus’ pioneering approach to electronic drums. However, in the early ‘80s across the rest of the world, Saga were big, real big. While the band maintained that following in Europe, it dropped off the map in North America. What happened? Well, that’s up for debate.

In a bleak piece by Jonathan Gross in the July 1986 issue of Canadian Musician titled “Canadian Musicians And Their Money,” one of Saga’s managers, Clive Corcoran, is connected to quite the scheme. “Saga was making enough money to prompt a move offshore, to Nassau where Corcoran formed a Dutch Antilles company that would exempt the band from tax status in Canada,” Gross writes. “The downside was that Saga had to become legal residents in Nassau and were allowed in Canada only three months of the year.”

Whether that’s true or not, Corcoran and Saga do indeed go way back. Here’s a snippet of the liner notes of the band’s self-titled 1978 debut that happens to introduce us to another player in the Piledriver story: “Management & Direction by CLIVE CORCORAN & ZORAN BUSIC for CBM,” with that acronym standing for “Corcoran-Busic Management.” Busic is additionally credited for the album’s “concept & design.”

Corcoran-Busic was still the management team when Saga’s 1981 album, the Rubert Hine produced Worlds Apart, went gangbusters, pushing over a million units and charting in several countries. Per Gross, after the breakout, “Corcoran and his then partner Zoran Busic had been advanced a huge sum in deutschmarks by Polygram in Hamburg.” (I was unable to contact Corcoran for this intro.)

Saga were on top of the world. And then, in a classic music business turn, subsequent albums failed to hit similar sales targets. When Gross caught up with Busic, there were questions of whether the band would even live to make another album.

“The band made some money but we also spent a lot of it,” Busic is quoted as saying. “I don’t really know what happened after Worlds Apart. Looking back I don’t think the band could deal with the changes in radio and the new music that was getting played on MTV.” The section closes with Busic’s ominous addendum regarding Saga’s deutschmarks: “The bottom line is that there really isn’t one right now.” Perhaps Busic was in a position to know. After all, he also ran Saga’s Canadian label, Maze Music. (Busic did not respond to interview requests.)

(Worth noting: In an interview with the Music Express, Saga bassist Jim Crichton chalked up the dwindling sales to something else. “Unfortunately, our manager, Clive Corcoran, who was originally from England, didn’t think we were getting a fair cut of the concert revenues. So he re-positioned us in Europe and I don’t think we played North America again consistently for about another 10 years. In retrospect, this really hurt us because when we tried to re-establish ourselves again we were no longer able to play the arena circuit.” The title of that interview? “Saga: Yes! But We’re Huge In Hamburg!” Saga are still active, by the way. They just released their 22nd album, the “acoustic re-imagining” Symmetry, earlier this March. Saga, through their current management, declined to comment on this intro.)

Busic’s Maze Music handled the Canadian releases for Saga beginning on their third album, 1980’s Silent Knight, until 1985’s Behaviour, when what remained of the band made the jump to Bonaire for 1987’s Wildest Dreams. You may not be surprised to learn that at some point during that span, the Corcoran-Busic partnership purportedly fizzled.

(Okay, cue another long parenthetical: The label is sometimes referred to as Maze Records. Both technically existed. It’s hard to ascertain which one is the parent label as Maze also cycled through a number of not-clearly-defined sub-labels. For clarity, I will use “Maze” to refer to its many entities when discussing the company at large. Busic’s involvement with Maze is substantiated by a couple of other sources, like this Metal Forces Magazine feature from 1986 and Garry Sharpe-Young’s 2007 book Metal: The Definitive Guide. Finally, fascinating tidbit for Canadians: Gross states that Busic’s business partner was Moishe Lerman, son of Thrifty’s founder Irving Lerman.)

And here’s where that long chain finally links back to our story: Maze wasn’t just a Saga depot. It made its foray into the world of heavy metal by picking up Virgin Steele’s 1982 self-titled debut and slapping on some more… hormonal art. In an ‘80s suddenly receptive to heavy metal, it did numbers. It had a bottom line, in other words. That must’ve given someone an idea. And, as Leslie Howe and Louise Reny were shopping One To One around when the Corcoran-Busic connection was still strong, they’d hear all about it.

By 1984, Gord Kirchin was steadily building a career. Following Mainstream, he played bass for Ron Chenier’s Fist (known in Europe as “Myofist” to differentiate it from the NWOBHM Fist) and did a run with Brian Greenway of April Wine. At that point, Kirchin just needed a break. Then, out of the blue, an old associate got in touch.

“I was on the road and I got a phone call from Leslie Howe stating that he was working on a heavy metal recording project that would not have a band,” Kirchin told Metallian in 2006, “but they needed a really heavy voice and [Howe] remembered me from being in [Mainstream] and having the heavy vocals.” Howe asked Kirchin. Kirchin said yes. Then Gord got the rest of the story.

“Producer/guitarist Leslie Howe was negotiating a contract for his commercial [pop] outfit One [To] One and in those conversations the record weasel said that he had a metal division wherein any album with decent cover art managed to sell about 20,000 copies no matter what shit was inside it,” Kirchin said to BeatRoute in 2016, using the “record weasel” appellation as a stand in Busic for reasons we’ll explore in the future. In Kirchin’s account, Howe said he was game. Fake a band, slap on a cover, push units. Easy. Busic then assigned Howe some homework.

“[Busic] gave [Howe] some Venom and some Slayer, and I think it was Exodus… no, it wasn’t Exodus. Blind Illusion, maybe? I can’t remember exactly, it was another Bay Area band,” Kirchin said on the Grim Dystopian podcast. “[Busic] told [Howe] to write something along these lines. So, the Venom and the Slayer crept to the top.” (For what it’s worth, put my money on Exodus. Venom, Slayer, and Exodus would go on tour in early 1985.)

In his email, Kirchin confirms the above. What I was surprised to learn was that Kirchin wasn’t prepared for what Howe could cook up. “When I got to the studio, I was blown away,” he writes. “Leslie was a decent enough rock guitarist, covering all the usual bar-band material well enough, but, not in any stellar way. But, this… this was truly above and beyond his usual pop-tinged output. He had done his homework well. I thought he really found a comfy spot between over-the-top thrashing and commercial hooks. I was quite happy to bark over it, haha.”

So, the music was legit. And the character they had in mind to front the “band” was taking shape. “The basic concept was already in place before I showed up: the name Piledriver, the idea that the singer would be all leather ‘n’ studs, and really push the sickosexbeastanimal image,” Kirchin writes. “That humor would be involved in the lyrics. This was to be the most over the top insanely disgusting and irreverent character to step into the limelight after the waning of Alice Cooper and other macabre acts that had gone soft. Metal needed a new monster man to offend parents and milquetoasts.”

When it came to the lyrics, Kirchin didn’t have to do much to inject that humor or the shock, but he did add an extra oomph. “While I did adjust minor words or phrases here and there to fit my mouth better while at the mic, I didn’t really do all that much to their lyrics conceptually,” he remembers. “At the time it was my understanding that while Les did all the production/composition, Louise was in on about half the lyrics. An example would be ‘Sodomize The Dead.’ There were variations on who/what was being sodomized (your dog, your mom, your priest) until the take where I sang ‘the dead,’ and it stuck.”

There’s something else happening in those lyrics, too. In an interview with Billboard, Reny described her lyrical approach to non-Piledriver material: “Deep down inside, I guess I’m a really bitter person. I used to work in lots of flash stripper bars and got a real depressed view of men in their lowest form. I think it’s wrecked my life. But I know I’m not going to have friends if I’m bitter, so being sarcastic is the next best thing. I think that’s where my lyrics come from. I like to surround myself with people who have a sense of humor.”

Piledriver songs like the aforementioned “Sodomize the Dead” and the wilder “Sex With Satan” are almost early proofs of concept for Reny’s later approach, unifying ‘80s extremity/degeneracy with acerbic, yet totally goofball jokes. A sampling from “Sex With Satan”: “Degradation, humiliation, thrusting, shoving, animals humping.” Lines like that signaled Piledriver was going to be be no by-the-numbers swords and sandals affair. If the aim was to rile the kind of “wholesome” people who would’ve blanched at their kids’ Alice Cooper routines a decade earlier, the project’s name and its eventual mascot were a perfect fit.

Of course, they still needed to record the damn thing. Kirchin hopped into the booth on the 18th and 20th of August 1984 and inhabited the character he was meant to play. As he recalls, Howe, Reny, and Busic planned that Piledriver the character “would be clad in leather, studs, roofing spikes, and the provocative S&M regalia.” That’s exactly the performance Gord gives: sweaty, sharp, hard, and nasty. And it seemed like Piley was already making an impression on Kirchin. “When I arrived I just helped hone [the character] into finer detail, and during the contract signing dinner, I doodled ‘him’ on the proverbial napkin to illustrate our thoughts.”

Piledriver was born. Its parents? Two synthpoppers and one music lifer. Now the record company needed an album cover. And that, if you can believe it, is when the links in this story expand exponentially. Things are about to get much deeper, weirder, and darker.

After stepping out of the vocal booth, Gord Kirchin felt good. He took Leslie Howe and Louise Reny’s melodies and “went for madness,” cracking everyone up as his Piledriver performance became more outsized. Already a ludicrous song packed with hilariously debaucherous one-liners, his over-the-top selling made sure tracks like “Sex With Satan” oozed with… uh… a lot of things. Gord knew that Metal Inquisition was going to be a hit.

“I was on cloud nine, knowing what we had just laid down was a very, very solid 40 minutes of truly great metal that made you move,” Kirchin writes. “It had shades, hues, variations, groove, intensity, drama, detail, and all those musical and lyrical hooks. And those ear-shredding guitars! Yes, I knew. I actually felt that if this album tanked, there was something truly wrong in the metal world. While Leslie and Zoran were only interested in making a quick buck on a few thousand copies, I knew from the get-go that this was going to be sooooo much bigger than that.”

According to Kirchin, he chipped in more than vocals. He penned the original liner notes that gave the players their jokey pseudonyms, finalizing the fake band charade. A lot of the aliases were callbacks to their shared bar band past.

“In Mainstream, Les’ nickname was ‘Long John Silver’ for his love of money,” Kirchin remembers. Onece intended to set Howe’s nom de guerre as producer, it eventually stood in for his publishing company. For Howe’s guitar heroics, Kirchin went a uniquely Canadian route. “I named him Bud Slaker. ‘Bud’ was the band’s nickname for pretty much everyone, and it naturally fell in line there.” The “phantom bassist” position was passed to Reny and repurposed her nickname/stage name “Sally.” “I’m a big Gibson guitars nut, so that became the name Sal Gibson, cut down a few letters to impart a male-sounding odor to it.”

As for the rhythm guitar, Gord winked at the audience. “Knuckles Akimbo was just a straight up joke to explain the second guitar parts.” The drum machine got the same kind of gag: “Former” Lee. Among some groaners, a few of the “crew” received Kirchin’s more cryptic punchlines. “Drum tech” Cliff “Showmeagain” Breech name-checked If/Ted Nugent drummer Cliff Davies “and a private joke to myself referring to a former drummer of mine who could not remember a single song intro and always needed to be reminded ‘how it goes.’” The mandate throughout was to “metalize” as much as possible.

Kirchin’s other key contribution was the Piledriver character design that he “doodled… on the proverbial napkin” during that fateful contract-signing dinner. How detailed was that sketch? “From head to toe, every spike, every strap, and the bondage mask,” he recalls. “Even the skull and crossbones on the mask.”

After submitting all of his elements for the layered ruse, Kirchin headed back home to await the next steps. After all, in accordance with the plan to dress a metal cash grab in “decent cover art” and reap the rewards, there was still a Piledriver suit to make and an album cover to shoot. Little did Gord know that he wouldn’t be included either.

George Giaouris burned the midnight oil on the Piledriver job. “I remember working into the wee hours, making those crazy shoulders myself!” he writes in an email. “All the studs made them quite heavy and I had to figure out a system of straps to keep them from sliding off the shoulders.”

Giaouris is the proprietor of Northbound Leather Ltd., a Toronto-based leather/fetish retailer. The about section of the (NSFW) website proudly lists some of its buyers: “Carmen Carrera, Kreesha Turner, Tracy Melchor, Carole Pope, Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Madonna, Enrique Iglesias, Sarah Brightman, Paris Hilton, in addition to stock brokers and club kids.” It also has one heck of a history.

Before it was Northbound, it was Leather Craft Ltd. Giaouris’ father opened the store in the ‘60s and eventually moved operations to Toronto’s Yonge Street, settling across from the patio of the Gasworks, “an excellent heavy metal bar,” in the words of Wayne Campbell. The location was perfect.

“We’ve been doing stuff for bands since the ‘70s and maybe into the ‘60s,” Giaouris tells me over the phone. “We’d make stuff for, say, Sly And The Family Stone. And I’d see people coming into the store like Iron Maiden. There were a lot of bands that came through. Anyone who played a gig at the Gasworks would sit on the patio with their pitcher of beer after soundcheck. They’d look across the street at this leather store. They’d wander in. If you wanted black leather and studs, we were the place to go.”

Adventurous clientele brought with them adventurous tastes. Leather Craft was more than willing to meet their needs. “If there was a trend, we were the first to hear about it because people were coming to us,” Giaouris says. “We had a sign in the window since my dad’s time and it’s now printed right on our current signage: ‘name it and we’ll make it in leather or suede.’ And, essentially, if people were unable to find it anywhere else, they’d come to us and say, ‘Hey, can you make this?’”

That’s pretty much how Giaouris recalls what happened when some prospective buyers wandered in with dreams of a leather getup complete with huge nails poking out of the hood and shoulder pads. Hey, can you make this?

Answering that question took some engineering. “The nails are giant,” Giaouris recalls. “They’re real nails, they’re made from, you know, those big spikes that they use to attach your eavestrough to the side of the house.” He’s not kidding. Giaouris bought the nails from a hardware store. He gave them a spritz of spray-paint to ensure they wouldn’t rust. Getting them to stand required an elaborate setup all made out of leather.

Giaouris, one of the nicest and most patient people I’ve talked to, explained the feat of leather to me slowly, like how a NASA scientist might explain space to a puppy. I’m still not sure I get it. No matter, the rig worked… for a bit. “And, basically, what ended up happening is that with all the motion, [the nails] started flopping around anyway,” he says. “You can see in some of the photos that they’re not standing up rigidly. They did initially.” Hey, happens to all of us.4

While the Piledriver suit would be too outré for many, it wasn’t much of a stretch for Leather Craft. The business happened to be maturing at the time and Giaouris was interested in “separat[ing] the two different types of clientele, to give some privacy to the ones that were taking it into the bedroom or practicing their air guitar.”

“In 1984, we were doing all of the spikes and the kinky stuff and the belts and all of that,” Giaouris says. “I decided to open a separate location and call it Northbound Leather. ‘North’ for where we are, ‘bound’ for what you do with it, and ‘leather’ for what it’s made from. Kind of tongue and cheek, nondescript. Sounded like an outdoors store, but it wasn’t. Kink in a plain brown wrapper is what I wanted, nomenclature wise. And so we opened it up on the same block, behind the shop, fronting onto Saint Nicholas Street, which is the lane that runs north/south parallel to Yonge Street just to the west. We’re still here.”

Northbound is now world famous for its array of “fine leather and fetish fashions,” still proudly proclaiming “you name it, we’ll make it” on its website’s page for custom ordering. That website is another way Northbound has innovated, not just in the fetish space, but on the internet at large. “We were one of the first two hundred commercial websites on the internet,” Giaouris beams. “We wrote our own version of a shopping cart for online sales and we’ve been cited in a couple textbooks as an example of early e-commerce.”

While Leather Craft wound down, existing today as a corporation without the storefront, Northbound continues to rack up credits. “We still see a lot bands,” Giaouris tells me. “We do a lot of work for theater, film, TV shows. We’re working with a couple of shows right now and I’ve been sworn to secrecy.” Even though my prodding couldn’t get him to spill the beans, I did learn that, back in the day, Leather Craft made jackets for Charles Bronson in Deathwish and Redd Foxx was a return customer. Sanford And Son to Piledriver in two degrees of separation, all thanks to some gutter nails. And yes, they’re standing up just fine on the cover for Metal Inquisition.

Patrick Harbron snapped that photo. After starting as a talented “rock and roll photographer” and one-time drummer of Space Phlegm, Harbron has gone on to have himself a career. Over the years, he’s published three books. He has plied his trade for “Apple, IBM, American Express,” among others. He’s also done significant work photographing TV productions. And he’s set up a website, Rock And Roll Icons, to share and sell his concert pics and portraits. There’s a good chance you’ve seen his stuff.

In the early ‘80s, Harbron was making waves in album design. He has photos in Black Sabbath’s Live Evil. He also shot the photo adorning the cover of Anvil’s Forged In Fire.

“Anvil were always cool guys to work with,” Harbron writes to me over email. “They were so committed, it made the shoots fun. I wasn’t happy when they cut hash joints on my antique Coke machine, but I got over it.”

Harbron’s album cover breakouts were two Attic Records compilations, 1984’s Metal For Breakfast and 1985’s Metal For Lunch. Not only did he shoot the covers, but he created the concept. He’d be nominated for a Juno Award for the former. That one also caught the attention of Zoran Busic.

“I was contacted by Zoran, co-manager of the group Saga,” Harbron remembers. “He was already a client and liked what I did with the Metal For Breakfast cover. His office was across the hall from my studio in Toronto.”

Busic had a character, suit, and general idea. The rest was up to Harbron. “I decided on everything you see after the idea was given to me. The leather clothing for the ‘executioner’ was already set. I wanted to create a stage with proper lighting and I blended the club’s rig with my flash equipment. I achieved the ‘live’ look with proper light to assure a clean image. It was a production that would have looked different if I had just used stage light.”

The club? The Gasworks. “The Gasworks was a real rock and roll club,” Harbron explains. “Groups like Rush, Triumph, Max Webster, and Goddo played early gigs there. I’ll bet Saga did as well. So many bands went through there. I think I proposed the idea to shoot in the club because I knew the stage would make the shoot easier to pull off.”

Harbron scouted location, set schedules, acquired props, and hired on additional crew. Some things happened through serendipity. “I don’t know if we had a choice of guitars but the flying ‘V’ was perfect,” he writes, later adding, “I don’t remember where the PA cabinets and the drum kit came from. They may have belonged to the band that was playing that night.” Oh, the things your gear gets up to when you’re off window shopping at Leather Craft.

While the atmosphere is perfect, what catches your eye are the two people at the center of the cover. “I don’t know who the ‘victim’ was,” Harbron writes. “He may have been a relative of Zoran’s. We didn’t hire anyone. The ‘executioner’ is Craig Jones, who was a DJ at CHUM-FM in Toronto. Craig was also the model for the covers of Metal For Breakfast and Metal For Lunch.”

One of the enduring mysteries of the Piledriver tale that Harbron couldn’t solve for me is the victim’s shirt. Harbron doesn’t remember the longsleeves’ origin, but it’s a clever Easter egg. There, screened on the front of the shirt, is the album cover. It’s a wonderful bit of Escher-lite recursion. On the back of the shirt, which you can see on the album’s reverse, is the first line of the chorus to the album’s title track: “If you ain’t a metal head then you might as well be dead.”

After Giaouris and Harbron both nailed their respective parts, Busic had his all-important cover, the key element he believed would help sell a record regardless of the music contained within the cardboard. He’d release the experiment on Maze Music’s new sublabel, Cobra Records. Piledriver’s Metal Inquisition is IDed in the Cobra catalog as CL 0001. Everything was going according to plan, except… uh… someone wasn’t filled in about that plan.

“I had moved to Montreal from Ottawa at the beginning of September,” Gord Kirchin writes. “I was waiting for the call to go to Toronto to get fit for the costume and shoot the cover. I almost fainted when it arrived by mail, all completed, with someone ELSE in the costume on the cover. I felt so completely cheated and dismissed. It was the first sign that I was being used, abused, and ripped off for my contributions.”

Kirchin started seeing the album at Rock en Stock, Montreal’s big independent record store, “before the end of the month.” (Rock en Stock, Banzai Records, the “speed metal swirl,” and the great Canadian bootleg bust is a story for another time.) Here was his career break, the project he poured his soul into. Real, tangible, ready for purchase.

However, besides his voice, there was no sign that Kirchin was involved. He’s not pictured on the cover and his proposed liner notes were cut to bits. What remained probably worked too well, easily obscuring players unknown in most heavy metal circles. Kirchin is credited only as “Pile Driver,” and the album was now produced and engineered by “BUD” at Rattlesnake Studios, Belgium. (Interestingly, Frank Soda also gets a shout out.) Before Discogs and Encyclopaedia Metallum existed, that veil of anonymity would be a hard one to pierce.

In a cruel twist, Kirchin started hearing Piledriver everywhere, too. “It was like being Clark Kent seeing news reports of Superman’s latest save,” he writes. “Even more goosebump-raising was being on the street and hearing ‘Sex With Satan’ blasting out of a passing metalhead’s ghettoblaster, or hearing a bunch of punters [singing] in unison ‘if you’re not a metal head you might as well be DEAD’ at the back of a bar as I was playing covers onstage.”

But, according to Kirchin in an archived interview with Beat Route, the instruction from Busic was that loose lips sink fake bands. “I was told to keep it all a secret or I would ruin the masquerade. I got paid $250 for my work on it. That’s it.”

In his email to me, Kirchin confirms that this was the arrangement. “Lips were sealed, except to all but the very closest personal friends.” Even if he did let the cat out of the bag, there was no guarantee anyone would believe him. “The response was, ‘Riiiiiiiight, this is you. Yeah, sure.’ It always made me laugh.”

Metal Inquisition’s sales were no laughing matter. Based on word of mouth, the album continued to grow steam. It found fans at Britain’s Kerrang!, getting a write-up in issue number 91 (April 4 – 17, 1985). And Metal Inquisition was a favorite of smaller zines. The Corroseum, an outstanding resource for older metal, has 10 zines mentioning Piledriver in its archives and the countries of origin run the gamut: Germany, Mexico, Belgium, Brazil. The one English language zine, Canada’s Metallic Assault #1 from 1984, blessed Metal Inquisition with a fawning review, talking up the “heavy” music and instructing readers, in an unfortunately ‘80s way, to ignore the false album art. “Black metal from Ontario?” is the subheadline.

Part of the reason for Piledriver’s penetration in worldwide markets is because it was licensed to more established labels. Roadrunner Records picked up Metal Inquisition for Europe, while the US rights went to HME Records. It appears, though, that someone at HME must’ve gotten cold feet about the album’s contents. Instead of the real deal, it produced a censored version. The apocalyptic closer, “Alien Rape,” was retitled “Alien Raid.” And “Sex With Satan” and “Sodomize The Dead” were subbed off for two new songs: “Lust” and “Twister.” The replacements weren’t written and recorded by Leslie Howe and Louise Reny. They did, however, feature Kirchin’s vocals.

In the Beat Route interview, Kirchin asserts that Busic told him that Metal Inquisition “was barely making a mark” even though the songs seemed to be everywhere and zine mentions were piling up. Kirchin, then, was taken aback when Busic asked if he wanted to earn $250 for another fake band. This one would be helmed by Conrad Taylor, previously a guitarist and backing vocalist for Genya Ravan, a cultishly beloved singer whose work has been sampled by Jay-Z, N.E.R.D., and Black Moon, among others. Ravan was also a producer, working the boards for the classic Dead Boys recordings. That’s how Taylor also landed on Ronnie Spector’s punk-ish 1980 record, Siren. (I was unable to contact Taylor for this piece.)

The new “band” was named Convict. Kirchin took on the role of Terry “The Con” Browning. Go Ahead… Make My Day! was released in 1985, Cobra Records catalog ID# CL 1002. This time, the album art was by Ioannis, who’d go on to do the covers for Fates Warning’s The Sprectre Within and Awaken The Guardian.

“Lust” and “Twister” were leftovers from that session. As Convict is more of a thuddier hard rocker, they don’t really fit on Metal Inquisition.

But thanks to a production screw up, HME accidentally released a batch of the original Piledriver recordings under the new song titles. “Sex With Satan” became “Lust.” “Sodomize the Dead” became “Twister.” This early mispress happened to be sitting in a record store when Pastor Jeff Ling was out hunting for albums.

Ling was part of the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), a group formed in May 1985 by four “Washington Wives:” Susan Baker, Tipper Gore, Pam Howar, and Sally Nevius, partners of James Baker (then Secretary of the Treasury), Al Gore (then a senator, future Vice President, presidential candidate, and creator the internet), Raymond Howar (real estate developer), and John Nevius (lawyer, former head of D.C.’s city council), respectively. (The group reportedly received early funding from Mike Love of the Beach Boys and Joseph Coors of the Coors Brewing Company empire via his Heritage Foundation.)

The PMRC deserves a deeper dive (Zach Schonfeld’s 2015 oral history for Newsweek is a starting point, and Chelsea Anne Watts’s 2016 dissertation, Nothin’ But A Good Time: Hair Metal, Conservatism, And The End Of The Cold War In The 1980s, is your next step), but, in short, the group is most known for a series of actions it undertook in 1985. Framed as consumer advocacy and an FYI to parents, these efforts were reactions to, in Susan Baker’s words, “the growing trend in music toward lyrics that are sexually explicit, excessively violent, or glorify the use of drugs and alcohol.”

For our purposes, three actions stick out: First, a letter was sent to the Recording Industry Association Of America (RIAA) asking for albums to rated similarly to movies. Then, the PMRC created the “Filthy Fifteen,” 15 songs the group found offensive and were a proof of concept for the aforementioned rating system. And finally… well, we’ll get to that seismic pop culture event momentarily.

Ling’s work started earlier. “As a youth minister, I was concerned about the kids that I was responsible for,” he tells me over the phone. “And so I began doing talks for my youth group and [their] parents.” If you present it, they will come, and soon the groups of concerned parents surprised by what their kids were listening to grew larger. Kandie Stroud, then a journalist, was hipped to a talk Ling was giving in Fairfax, Virginia, attended by “several hundred people.”

After Ling’s talk, Stroud submitted an entry for Newsweek’s My Turn column. “Stop Pornographic Rock” ran in the May 6, 1985 issue. It begins with a now-familiar anecdote, one of a daughter bringing her mother’s attention to the risqué lyrics in Prince’s “Darling Nikki.” The piece also highlights a handful of tracks that would later make the Filthy Fifteen. The most prophetic line is this one: “Legislative action may be needed, or better yet, a measure of self-restraint.”

In the wake of the column, Ling made connections “with Susan Baker and Tipper Gore and the others.” When the PMRC started, he was there. His talks expanded to include “groups of senators, congressmen, and other civic and religious leaders in those areas.”

In order to stay up to date, Ling employed a shoe-leather approach to his research, frequenting record stores in the Washington, DC and Northern Virginia area. “My question, as always, was what else is in the bin with the popular artists?” he explains. “The kid that goes looking for the WASP album or the Black Sabbath album or the Slayer album, what else are they going to come across?” Finding the bad stuff was easier than expected. “It was always there. You could always find that material. It wasn’t behind the counter. It wasn’t in a brown wrapper. It was just there.”

Along with flipping through records, Ling perused the available periodicals. “We’d look for information on artists that were making an image for themselves as the bad guys. You didn’t have to look far in publications to see the

Mötley Crües celebrating sex, drugs, and rock and roll.” In particular, the European magazines was where the more “cutting edge” and “risky” bands resided.

“It was a drag, frankly,” Ling says with a laugh when I asked about the depth of his research. “I have been in pastoral ministry for the last 40-something years, and I don’t know any pastoral guys who would love to spend a number of hours every day filling their heads with garbage.” Still, looking at the Filthy Fifteen now, you can see the what this exhaustive approach produced. Rubbing shoulders with the heavy hitters from the pop and rock world are Mercyful Fate’s “Into The Coven” and Venom’s “Possessed.” Ling would soon get an opportunity to display more of the deep cuts he collected.

On September 19, 1985, commencing at 9:40AM in room SR-253 of the Russell Senate Office Building, the US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science And Transportation opened its hearing on “contents of music and the lyrics of records.” “The reason for this hearing is not to promote any legislation,” Senator John Danforth, chairman of the committee, said. “Indeed, I do not know of any suggestion that any legislation be passed. But to simply provide a forum for airing the issue itself, for ventilating the issue, for bringing it out into the public domain.” Senator Fritz Hollings was less restrained about the “outrageous filth,” stating in his opening remarks, “if I could find some way constitutionally to do away with it, I would.” Porn rock had made it to the Capitol.

As part of the PMRC’s opening salvo, Pastor Jeff Ling was set to give a slide show presentation. You can see it in this C-SPAN clip (it is way more NSFW than the website for Northbound). Ventilated in the US Senate that morning were your Mötley Crües and WASPs, but also album covers for Abattoir, Impaler, Mercyful Fate, and Bitch. An underground headbanger would be proud. It was quite the haul. At 6:40, Ling added this to the public domain:

This band, Piledriver, fuses together the elements of sexual violence and occult in the song “Lust.” I forgot. [Ling holds the album aloft off camera] It is right here in front of me. The song is called “Lust.” The lyrics say, “Hell on fire. Lust, desire. The devil wants to stick you. The devil wants to lick you. He wants your body. He wants your spirit. Naked twisting bodies, sweating. Prince of darkness. Prince of evil. Spread your legs and scream. This is no dream. Degradation. Humiliation. Thrusting, shoving. Animals humping. He is like a dog in heat. You are just another piece of meat. Craving demons fill you with pain. Now you are bloodied and stained, hurt and beaten. He will possess you. He will molest you. Sex with Satan. Sex with Satan.”

I asked Ling if he was nervous to be presenting this information to senators. “Well, of course!” he says, later adding, “and in the presentation itself, there was a hiccup with the slide projector — it was automatically advancing instead of letting me advance it. That unnerves you. And of course, when I put the cherry on top with the final group of lyrics [from the Mentors], everyone busted up laughing. You felt a little stupid. You felt like, Ah jeez, what am I doing?”

Be that as it may, the over-the-top nature of Ling’s presentation, which included multiple instances of nudity and profanity, had a point. “But my philosophy from the beginning was you can’t sit in front of a bunch of senators and say, ‘Hey, your kids are listening to songs about having sex outside of marriage.’ That just wouldn’t do it. ‘Your kids are listening to songs about getting drunk.’ You just couldn’t do it.” In a way, it was Piledriver’s shock strategy in reverse.

Ling drives this home with the esprit de l’escalier he felt following an appearance on the CNN show Crossfire, the missed rebuttal that “would’ve made the point better than anything.” “[Tom Braden] started off the segment by saying, ‘Reverend Ling, birds do it, bees do it, even ordinary fleas do it. Let’s do it. Let’s fall in love. What’s wrong with that kind of thing, Reverend Ling?’ I wish I had had the balls at the time to say, ‘Fuck like a beast.’ Because that would have gotten them in trouble. Because they would’ve had to say, ‘You can’t say that here.’ Ah! Good point! How come we can’t say that here? Because you have standards that you have to go by at your network, don’t you? You have things you can say and you can’t say. I wish I had let loose with a stream of my worst stuff. But being a gentleman, being a pastor, being someone who was aware of the rules, I didn’t.”

While the hearing’s supporting witnesses brought out the big guns — “Some say there is no cause for concern,” Baker said her in testimony, “We believe there is. Teen pregnancies and teenage suicide rates are at epidemic proportions today.” — the opposing witnesses made the lasting impact. Frank Zappa, Dee Snider, and… John Denver have been feted for showing up and pushing back. Zappa, seemingly particularly irked by Senator Hollings’s statements, dropped the hammer on the PMRC’s push for a rating system. “The PMRC proposal is an ill-conceived piece of nonsense which fails to deliver any real benefits to children, infringes the civil liberties of people who are not children, and promises to keep the courts busy for years dealing with the interpretational and enforcemental problems inherent in the proposal’s design.”

Zappa, who reportedly told WASP’s Blackie Lawless “Be glad you didn’t go — it was a big dog-and-pony show,” would send up the experience in “Porn Wars,” an audiocollage on his 1985 album Frank Zappa Meets The Mothers Of Prevention. A snippet of Ling’s Piledriver recitation made the cut.

This Zappaian sense of pointed bemusement is how the legend of the hearings is mostly retold in the heavy metal world, especially after the burgeoning culture war traded in Satanic Panic for hip-hop as public enemy number one. The RIAA, maybe operating with ulterior motives, adopted the now-familiar “parental advisory” labels on November 1, 1985, self-policing its recordings without the rating system. While it’s never been accurately measured, the “Tipper sticker” didn’t appear to have much of a detrimental effect on sales. And, over the ensuing decades, there has also been the expected societal norming of once-unsavory endeavors.

“I’m glad on the one hand that parents got that information and were able to make use of that,” Ling says. “I’m glad that it happened when it did because getting it done today would be almost impossible. Now, a kid can get whatever they want to get their hands on. It doesn’t matter. Streaming services, downloading: you want it, you can find it. It’s unfortunate, but it is the way it is.”

While we probably don’t agree on much by dint of me writing a monthly metal column, Ling is affable, more self-aware about his place in history than his ‘80s combatants probably gave him credit for. “I’m not excited that my legacy in the congressional record is the things I said at that hearing,” he says through a chuckle. “Not exactly the thing you want to go down in history for. But, it’s okay.” As we chat about the present, he adds: “I have spent my life counseling, getting couples ready to get married, helping people bury their loved ones, baptizing babies, and sharing my faith with people. That’s my life. This other thing was a small part of it. I feel like the things I’ve been able to do are not the things people will be able to read about. The congressional record will be there forever, but I won’t be. But I have been privileged, honestly privileged, to spend my life loving and helping people along the way and that’s more important to me at the end of the day.”

Gord Kirchin’s take on the Senate hearings is the same as a lot of underground musicians who unexpectedly made it into the congressional record. “That we were included and thus heralded there was no doubt a big help in moving those 500,000 slabs of harmonic evil, haha!” Indeed, for a brief moment, Piledriver looked poised to break into the big time. Instead, everything fell apart.

“I’ve always maintained that if we would have gone out and gigged rather than play that silly ‘mystery’ game, we could have been a major act,” Kirchin writes, now referring to Zoran Busic with Kirchin’s preferred sobriquet, “Sadly, the record weasel only wanted to make a quick buck and had zero foresight into developing and growing this band as it would entail investment and work.”

Per Kirchin, Busic signed off on Piledriver turning into a touring band, but wouldn’t offer financial support. Auditions went nowhere. “I found it very hard to find musicians at the time who were into stage ‘costumes,’ stage names, and the humor-laced lyrical thrust,” Kirchin laments. (This Is Spinal Tap was released in 1984. Gwar cut its first demo in 1985. Make of that what you will.)

So, in order to capitalize on Metal Inquisition’s heat, there needed to be a sequel. Problem: Leslie Howe and Louise Reny weren’t available. “Leslie has simply denied any dealings of any kind regarding Piledriver, pretty much since weeks after it was put out, once he too realized that he had been pooched royally,” Kirchin claims. To be fair, Howe and Reny did have irons in other fires.

Following Metal Inquisition, Howe and Louise Reny were back at work on One To One. Forward Your Emotions, the duo’s debut, was released in 1985. Two of its singles, “There Was A Time” and “Angel In My Pocket” cracked Canada’s top 40 and the latter sneaked into the lower rungs of the Billboard Hot 100. The album was nominated for three Juno Awards in 1986, including two recognizing Howe’s production and engineer work. 1988’s 1-2-1 extended One To One’s winning streak. “Hold Me Now” peaked at #13 on the Canadian charts. As that song was making waves, a budding Ottawan musician entered the Howe/Reny universe.

According to Paul Cantin’s Alanis Morissette: You Oughta Know, which I am lifting secondhand from Soraya Roberts truly excellent “Alanis In Chains” essay for Hazlitt that takes a much more extensive look at this period, Morissette’s mother got her daughter’s demo into the hands of Howe. In an interview with the Detroit Journal, Reny remembered that Morissette asked her for career advice. “I met her when she was 12. My advice to her was to stay out of the music business. Good one, eh?” Morissette signed a five-album production deal with Howe’s company, Ghettovale.

Two of those albums were made for MCA Records: 1991’s Alanis and 1992’s Now Is The Time. Howe produced both, churning out sub-Jam & Lewis dance-pop with incongruously adult lyrics for a teenager. Music Canada certified Alanis platinum thanks to 100,000 units shipped. Now Is The Time did half that. Pressure was mounting for a bigger return.

In an interview with Roberts, keyboardist and arranger Serge Côté, who has credits on those early Morissette records, paints Howe as an “intense” producer to work with. “He knows what he wants and he won’t hold back,” Côté is quoted as saying. This next line from Roberts sticks out: “At one point Howe’s credit cards were ‘maxed out’ in order to finance the Alanis recordings and Côté recalls him repeatedly saying, ‘This thing’s gotta work. It’s gotta work.’”

It didn’t work for long. Morissette, unhappy over the artistic direction and suffering due in part to the gross demands of an image-obsessed record company, wanted out. Despite owing Howe three more albums, she negotiated her exit, eventually releasing her smash 1995 16X platinum juggernaut Jagged Little Pill on Maverick Records. In order to not confuse record buyers keen on Morissette’s fiery alt-rock sound, “Maverick prevailed upon Morissette’s Canadian label to take her two previous releases out of circulation,” according to a Boston Phoenix article. That wasn’t the only bit of music business that tied up loose ends. Roberts writes that Morissette confirmed to biographer Cantin that Howe released her “in exchange for an undisclosed percentage of Jagged Little Pill’s revenue.”

In interviews, though, Reny and Howe took a more friendly tack. “It’s hard to believe or imagine that our buddy is like this huge star,” Reny said to the Detroit Journal. Howe pushed that both artists were looking for different things. “I made two albums with her, then she was a star in Canada at age 14,” he said to the Hollywood Reporter. “After that, I wanted to do my own thing.”

Once Bonaire, One To One’s label, went belly up, Howe and Reny recorded one more album as the redubbed One 2 One. 1992’s Imagine It reconfigured the duo’s sound once again and managed to score them their highest charting hit, “Peace Of Mind.” A follow-up single, “Memory Lane,” made it onto Melrose Place.

Soon, there were new trends to chase. Capitalizing on the mainstream alt-rock explosion, Howe and Reny started Sal’s Birdland. 1995’s Naked Photos Inside, which contained baby photos of the members; ba dum tsh, has a sort of slacker Velocity Girl/Juliana Hatfield energy to it. By 1997, the group was renamed Artificial Joy Club And pursued a more Garbage-y, post-grunge trudge. “Sick and Beautiful,” a single from the project’s lone album Melt, made it onto 120 Minutes and got the band to Lollapalooza’s second stage. “I’ve been playing bars since I was 15, and I love it. I guess I’m just going to keep doing this,” Reny said to Billboard. Artificial Joy Club broke up two years later. Reny would go on to sing for Bubbles Cash And The Rhythm Method, a cover band whose history was wiped in the MySpace data apocalypse. While the Isle Of Deserted Pop Stars mentions that “Howe occasionally produces,” songs from the Melt sessions are his last official credits in most databases.

This is all a long way of saying that there were some other reasons why Howe and Reny might not have returned for a second Piledriver album. No matter, Busic had another artist under contract. An old Maze Music alum had made the jump to Cobra Records: Virgin Steele.

“Our manager at the time was like ‘you guys owe me money, you have to do this for me,’” Virgin Steele singer and songwriter David DeFeis said to Sweden Rock Magazine in an interview reprinted at the Corroseum. “It was one of those deals. It was creative and any chance I get to be creative, I take it, regardless of what the principle behind it may be sometimes.” That manager asked for three albums. The principle behind it? Three fake bands. The first was Piledriver’s follow-up, Stay Ugly.

DeFeis and guitarist Edward Pursino, a fellow Virgin Steele member, recruited bassist Mike Paccione and drummer Robert Espizito. The quartet worked quickly. “We did that record in two days,” DeFeis said. “I don’t know how long it took to write those songs, but it wasn’t very long. We sat in front of an old washing machine and wrote that record, Edward and I.” Even when the band flew Kirchin in, it was whirlwind affair. “We picked him up at JFK airport, he did all the vocals in a couple of hours and we drove him back to JFK later that night. There was no budget or anything. Then we mixed the album the next day and that’s what it is.”

“When I found out that there was a second Piledriver album in the works and it wasn’t Leslie Howe, I asked what are the fans going to think when it’s a completely different sound?” Kirchin said to Metallian. “‘Oh don’t worry, it is your vocals and they won’t even notice,’ said the record weasel and I am going ‘Well I think they will, it is like a completely different band because it is completely different.’”

Different? Yes. This wasn’t Metal Inquisition. DeFeis has said that he was “trying to get into the head of early Black Sabbath” on Stay Ugly, “just something completely thrashy and underground sounding.” Still, even though it’s a rush job, the album has some decent riffs. And DeFeis must’ve thought that “The Fire God” was worth salvaging. A slightly different version appears on Virgin Steele’s 1999 epic, The House Of Atreus – Act I.

The next two albums in DeFeis’ fake band career would be remembered better. Exorcist’s Nightmare Theatre and Original Sin’s Sin Will Find You Out are fake-band classics. DeFeis sings on the former, DeFeis’s sister, Danae, on the latter. (Both albums have been reissued by High Roller Records. Exorcist is good. Original Sin is great.) “You know, it was organic, all those records,” DeFeis said about his time with Cobra Records, adding “I don’t regret doing them, I’m happy that we did. I would have liked to make some money from them, but that’s always possible in the future if we put them out again. I own all the masters. I wouldn’t put the Piledriver out, though. That’s Gordon. Whatever he wants to do with it, just go for it.”

After Original Sin, Cobra Records was done funding its own fake bands. It grabbed one more for Canadian release, Grudge Records’ mysterious Lords Of The Crimson Alliance and its 1986 self-titled banger of bizarro power metal. Cobra whittled out the rest of its brief lifespan as a licenser, adding records from Circle Jerks, Agent Steel, Dark Angel, Voivod, Running Wild, Chastain, Celtic Frost, Death, Coroner, and Kreator to its stable. Its last release in 1987 or 1988 was either the Canadian versions of Living Death’s Protected From Reality or Tankard’s Chemical Invasion, depending on which source you consult.

While fake bands existed before — Nick Lowe’s Tartan Horde, etc. — Cobra Records got in early with the metal material and might’ve provided a blueprint for other labels looking to jump into the cash-grab game. Grudge (Lords Of The Crimson Alliance, Grudge) and the Dutch East Records-bankrolled Pentagram Records (Jack Starr’s Phantom Lord and Devil Childe, Joe Hasselvander’s Lady Killer) would follow in its footsteps. (I write more about DeFeis and Starr’s fake band runs over here, which includes an earlier version of this Piledriver piece.) And Cobra precedes the absolute nadir of the fake-band exercise, Metal Enterprises. That one is Dan Edman’s beat. He’d coin a good term for it: “Metalploitation.”

Despite the setbacks, Kirchin was still set on living out his metal dreams. Unfortunately, he was still tangled in Busic’s web. Disappointed with Stay Ugly, Kirchin grabbed the reins of Piledriver and took over production duties. He began work on a third album. One more insult, for the road.

“When I was at the mixing stage, the record weasel informed me that he would not be honoring the agreed $12,000 advance to pay for the recordings,” Kirchin writes. “After a heated discussion, I decreed that the recordings were now attributed to a band called Dogs With Jobs, that he now had nothing to do with any of it at all, and I joined Leslie [Howe] in finally severing my ties to the sleazy record weasel. I cashed in my [registered retirement savings plans] to pay for the sessions.”

Kirchin, who plays everything except the programmed drums and Sean Abbott’s lead guitar licks, released Dogs With Jobs’ debut, Shock, in October 1990 on the ironically named Fringe Product. It sounds like Metal Inquisition by way of early Megadeth. In order to fit the new “blue collar” band image, he “de-Pile’d” some of the lyrics. Two-thirds of the album are a mini concept record about a metalhead who accidentally wastes a cop, gets sentenced to death by electrocution, and turns into a lightning bolt-flinging madman. (Note: Wes Craven’s Shocker was released in October 1989.) Shock also includes a song that has become something of a Black Market staple. Ladies and gentlemen, once more, “Dogs With Jobs.”

Dogs With Jobs expanded into a trio and recorded one more album, 1993’s Payday. And then, Gord Kirchin logged onto the internet.

“I finally got a modem and got online,” Kirchin remembers. “At the time in my life, Piledriver for all intents and purposes was relegated to ‘the past,’ and Dogs With Jobs was winding down to its demise. I was reading some article, and they mentioned Piledriver. I was all ‘Wow, someone remembered ‘that failed album.’ Zoran [Busic] had long maintained that despite the interviews, chart placements, and coverage, it was a complete flop due to rampant piracy. Plugging the word ‘Piledriver’ into that Alta Vista search engine returned literally thousands of hits. I was completely shocked and blown away. It was then that the full scope of the record weasel’s kleptocratic manipulations of me were made painfully apparent. It hurt, a lot, as finding hidden truths often can.”

Kirchin created a website to tell his side of the story. The emails poured in. He also secured an entertainment lawyer and began the battle for royalties. He believes that lawyer’s research provided the 500,000 sales figure. “Sadly, in the 2000s, that figure is easily eclipsed by the dozens of bootlegs out there,” Kirchin writes. Fun fact: One of those bootlegs happens to be by Full Moon Productions, Velvet Cacoon’s label.

Kirchin would eventually lose the war for wages. He says he still doesn’t see any money for the early Piledriver material. And he’d face another indignity: “My final falling out with Leslie was when he flat out refused to provide a letter of intent and consent to the label to include me in royalties from the Maximum Metal/High Vaultage re-release of Metal Inquisition.”

Still, the fans kept coming out of the woodwork. By Metal Inquisition‘s 20th anniversary, it was time to do it live. “Ray ‘Black Metal’ Wallace began pestering me to get up onstage and serve the fans,” Kirchin writes. “Why not? Since the record weasel wasn’t going to change his stripes and help in any way, let alone fight all the bootlegs and bullshit that’s out there, why the fuck not bring it to the fans anyway? They’re out there! They want it still! What’s he gonna do? Sue us for the $150 we got for the gig?”

Much like Myofist, Gord tacked on “Exalted” to the front of the band name to differentiate his group from the other Piledrivers now out in the world. He held another round of auditions and secured a steady lineup. At long last, the Exalted Piledriver was real. Not only did the band play dates like Keep it True, it started to tour. It released a new album in 2008, Metal Manifesto. It “re-Pile’d” some Dogs With Jobs material. Now staffed by members of Spewgore, the band is still rolling.

That doesn’t mean Kirchin has been freed from the familiar downs of his music career. “I recently attempted shopping for a record deal for a new Exalted Piledriver album,” he writes, “but response from the industry was completely negative and I have zero interest in being a ‘label’ and all the associated work that goes into it. So, since the interest was definitely not there to support it, I gave up and deleted the files. Fuck it. Why go and spend big money to do a proper album just to lose it all hours after release when the pirate torrents hit the net?”

Still, even though there’s a lot of pain in Piledriver’s past, it has allowed Kirchin to realize a few dreams. As an avid Frank Zappa fan, he’s particularly tickled that he’s now linked to the man through “Porn Wars.” And the kid who used to slither around his room to “Dead Babies” would have a chance to influence another hero. “Years later, [I met] Alice Cooper at MuchMusic in Toronto. While gushing adoring gibberish like a 12-year-old fanboy, I handed him an 8×10 promo [picture] of Piley. Almost in unison he and Kane Roberts said ‘Wow! That’s HEAVY.’ Many months later on the Trashes The World tour, [Cooper] was sporting a distressed and torn leather jacket with 12-inch spikes coming out of the shoulders. While I may not have become a rich and famous rock star, I did, unbeknownst to them, directly influence my two biggest idols in very small ways.”

Kirchin has a new band now, another real one with “extremely talented old buds from high school” that’s working on some non-metal material that’s nearing completion. Nonetheless, he’s still down to do the odd “rock and roll vacations… to go play rockstar.” The Exalted Piledriver is a big ticket in Europe and South America. After all, he still has the suit. “Mind you, after a few decades of being forced to wear that damned costume because of the fans love for it, I could definitely reconsider at this point,” he writes. “Opening the suitcase before a gig is always an ‘oh fuck, here we go again… oh well… the kids like it’ proposition, haha.”

As I remember it, I talked with Gord over three interviews, not including followups. He was very gracious with his time as I tried to wrap my head around the totality of the story. I remember him telling me he was happy someone finally got it right. He died in 2022. He was 60.

And lord did I try. Nothing like ringing random Canadian phone numbers on a hope and a prayer.

One of those veins of gold you don’t expect to dig up while researching.

You couldn’t help yourself, could you?